After an epic struggle, equal representation on the Board of Directors has been achieved by descendants of the enslaved at President James Madison’s Montpelier plantation in central Virginia. This struggle and ultimate victory have implications for similar institutions across the country. I have participated in two archaeological projects at Montpelier, and have some insight into the issues there, and what all this means for visitors to the plantation.

President James Madison and his ancestors enslaved over 100 African Americans per year for over 120 years at Montpelier, from 1723 to 1844. While on expedition there, I calculated that the enslaved contributed over $500 million – half a billion dollars – in modern terms, in free labor to the Madison family. It was some of this income that paid for our US Constitution. Most Americans have heard that Madison is the “Father of the Constitution,” but few know that he had almost a year of free time before the First Constitutional Convention to study 1450 books on politics and formulate his revolutionary concept of three branches of government, with checks and balances between them. It was his slaves that gave him – and us – that vital time.

When The Montpelier Foundation was created in 1998 as managers under the National Trust for Historic Preservation, the focus of historical research and presentations to visitors was only on President and Dolley Madison. This began to shift when Matthew Reeves, PhD was hired in May 2000 to head up the Foundation’s archaeology department. He felt that the story of the Madisons was well-researched, while the story and contributions of the enslaved were almost unknown.

Over time this new focus led in February 2018 to the creation of the “Rubric,” a guidance document for how Montpelier and other similar institutions should work with descendant communities to honor the contributions of the enslaved. In June 2021 the Board of Directors of the Foundation declared that it would make history by becoming the first institution in the country to achieve “parity,” in which half of the Board would be made up of well-qualified persons nominated by the Montpelier Descendants Committee (MDC).

But behind the scenes Chairman of the Board Eugene Hickok (Deputy Secretary of Education under George W. Bush) and CEO Roy Young were leading an effort to reverse this historic decision, and their scheme succeeded on March 25 of this year. This led to massive protests by staff, donors and the public. Instead of backing down, on April 22 Foundation management fired Matthew Reeves and chief curator Elizabeth Chew via email, suspended others, and ordered many staff to stay off the premises. These actions were carefully timed to coincide with Reeves and Chew being out of town. Staff emails were cut off and investigated, the archaeology lab was made off limits (despite chemical restoration baths needing careful monitoring), and many public outreach programs were cancelled. These actions endangered over $1.2 million in grants, which were conditional on the promised parity.

An even bigger uproar ensued, with a petition garnering over 12,000 signatures, letters from associations and donors pouring in, and headlines and editorials in The New York Times and the Washington Post. The last black member on staff resigned, and her resignation letter cited the “casual racism” and “tokenism” she encountered, and the “unpardonable” … “aggression, combativeness, and condescension” of a key white Board member.

All this pressure resulted in a re-reversal on May 17, when the Board voted to bring in 11 new members recommended by the MDC, including luminaries Soledad O’Brien, award winning journalist; Rev. Cornell Brooks, JD, of the Harvard Kennedy School; and Nicole Jenkins, PhD, Dean of the School of Commerce of the University of Virginia. These 11 plus 3 existing MDC-recommended members brought the Board up to parity — finally. And on May 25 the new Board accepted the resignation of CEO Roy Young, installed the previously fired Elizabeth Chew as CEO and interim President, and appointed James French, former head of the MDC, as the new Board Chairman, replacing the outgoing Eugene Hickok.

So, with positive momentum restored, I can now whole-heartedly recommend a visit to Montpelier. You will be able to see the beautiful historic mansion, presented as it was in President Madison’s time, the lovely grounds, and the excellent exhibition “For the Mere Distinction of Color,” which gives a moving presentation on the enslaved. You can attend lectures and will soon be able to participate in even more substantial programs, most of which were halted during the protests.

What all this means for other similar venues, including Monticello, Mt. Vernon, and even our local Rev. Josiah Henson Museum, is that there is now a successful road map for involving the descendants of the enslaved who actually did the back-breaking work that built this country and those same institutions. Over 150 years after the end of the Civil War, I’d say it’s about time.

Photos courtesy Lew Toulmin

- The main mansion at President James Madison’s Montpelier 2600-acre plantation, 40 miles northwest of Richmond. The mansion has been beautifully restored to Madison’s time, and is the biggest attraction in Orange County. The white cabins on the right are restored slave quarters; the quarters far from the mansion, out of sight, were not nearly as nice.

- James and Dolley Madison – Washington’s first “power couple” – in their main reception room at Montpelier. James was only 5’4”, weighed less than 100 pounds, and was a poor orator. He could never get elected today, even though he was the “Father of the Constitution” and introduced the Bill of Rights. At dinner he would bet his many guests that Dolley could carry him around the dining table on her back – and he would win the bet when she did, four times around!

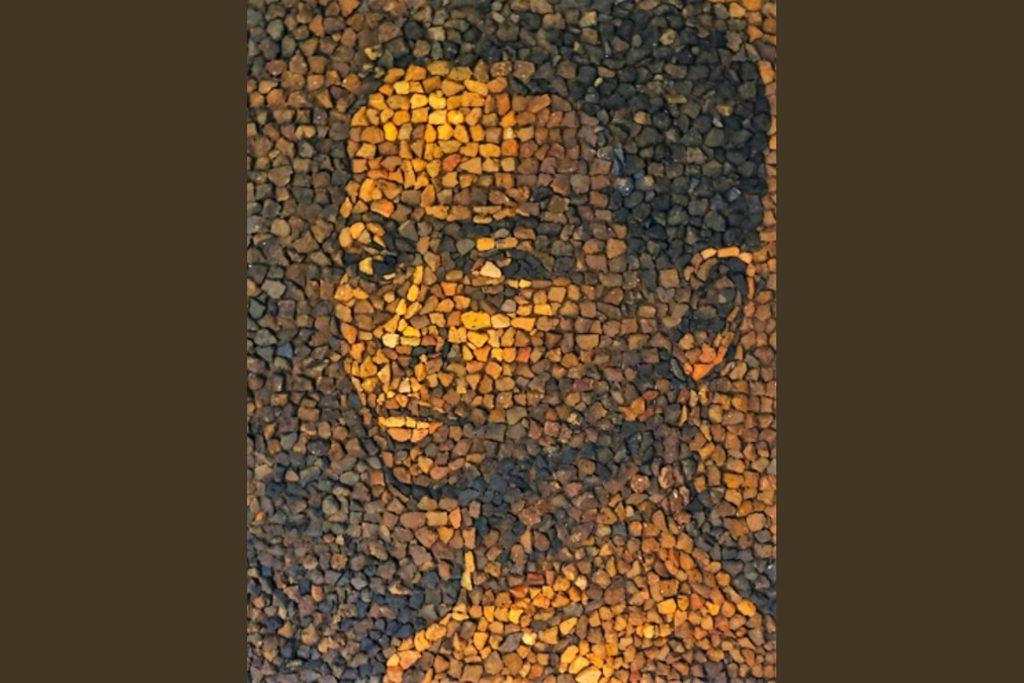

- A portrait of a young enslaved boy on exhibit at Montpelier, made from brick fragments found on the plantation. Enslaved children toiled many hours per day making bricks.

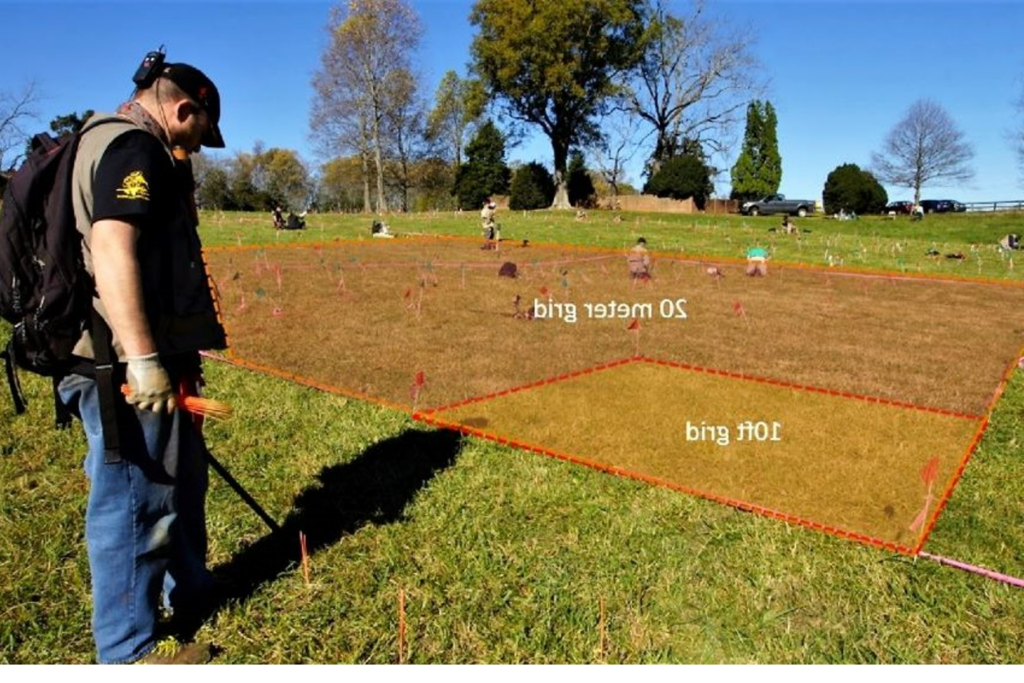

- The Montpelier Archaeology Department leads the nation in the use of metal detecting as the “cavalry” of archaeology, to quickly survey the landscape in search of “Montpelier gold” – scatters of iron nails that can be dated by their shape, which reveal archaeological sites underground. Twenty meter and three meter grids are used to identify “hot spots” of underground remains

- Patch for the Montpelier archaeology expedition in which author Lew Toulmin participated. The Temple of Liberty, inspired by the Roman Temple of Vesta, is on the grounds of the Plantation near the main mansion, and was designed by Madison and built (ironically) by his enslaved workers in 1811. The Temple is the symbol of Montpelier, and the ironies continue, since underneath the Temple is an icehouse. Enslaved workers would labor hard in the freezing cold of winter, to bring up blocks of ice from a pond 300 yards away, down a hill, to the icehouse, so that Madison and his guests could eat ice cream in the summer.

- Descendants of the enslaved at Montpelier gather on the steps of the main mansion. In red in the second row from the front is Bettye Kearse, author of The Other Madisons: The Lost History of a President’s Black Family, a moving book in which she traces her ancestry to a liaison between President Madison and his half-sister, an enslaved young black woman. Dr. Kearse is on the Board of The Montpelier Foundation.

- Industrial-scale blacksmithing was a major source of the Madison family’s income; the other source was tobacco farming. Here the slag from a blacksmithing operation has been discovered using “traditional dirt archaeology” – digging “units” (a small trench, as seen behind the slag) to uncover hidden artifacts and features that tell the story of the enslaved.

- A slave shackle key found underground at Montpelier.

- A carnelian ring – perhaps the best-ever archaeological find at Montpelier. Because of its chemical composition, this ring is known to have originated in India. It must have been traded across the Indian Ocean to east Africa, thence across the continent to west Africa, then brought to Virginia, where it was worn by an enslaved woman and ended up in the ground, in the remains of a slave cabin.